Devirtualization and Static Polymorphism

Ever wondered why your “clean” polymorphic design underperforms in benchmarks? Virtual dispatch enables polymorphism, but it comes with hidden overhead: pointer indirection, larger object layouts, and fewer inlining opportunities.

Compilers do their best to devirtualize these calls, but it isn’t always possible. On latency-sensitive paths, it’s beneficial to manually replace dynamic dispatch with static polymorphism, so calls are resolved at compile time and the abstraction has effectively zero runtime cost.

Virtual dispatch §

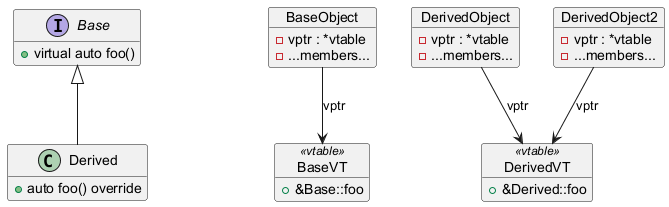

Runtime polymorphism occurs when a base interface exposes a virtual

method that derived classes override. Calls made through a Base& are

then dispatched to the appropriate override at runtime. Under the hood,

a virtual table (vtable) is created for each class, and a pointer

(vptr) to the vtable is added to each instance.

Figure 1: Virtual dispatch diagram. The method foo is declared virtual in Base and overridden in Derived. Both classes get a vtable, and each object gets a vptr pointing to the corresponding vtable.

On a virtual call, the compiler loads the vptr, selects the right slot

in the vtable, and performs an indirect call through that function

pointer. The drawback is that the extra vptr increases object size,

and the vtable makes the call hard to predict. This prevents

inlining, increases branch mispredictions, and reduces cache efficiency.

The best way to observe this phenomenon is by inspecting the

assembly1 1

Assembly generated with gcc at -O3 on x86-64. Similar

results were observed with clang on the same platform.

code emitted by the compiler for a minimal example

class Base {

public:

auto foo() -> int;

};

auto bar(Base* base) -> int {

return base->foo() + 77;

}

For a non-virtual member function foo like in the example above, the

free function bar issues a direct call

bar(Base*):

sub rsp, 8

call Base::foo() // Direct call

add rsp, 8

add eax, 77

ret

However, declaring foo as virtual changes bar’s assembly into an

indirect, vtable-based call

bar(Base*):

sub rsp, 8

mov rax, QWORD PTR [rdi] // vptr (pointer to vtable)

call [QWORD PTR [rax]] // Virtual call

add rsp, 8

add eax, 77

ret

Devirtualization §

Sometimes the compiler can statically deduce which override a virtual

call will hit. In those cases, it devirtualizes the call and emits a

direct call instead (skipping the vtable). For example,

devirtualization is straightforward2 2

The compiler emits a direct call to Derived::foo (or inlines

it), because derived cannot have any other dynamic type.

when the runtime type is

clearly fixed

struct Base {

virtual auto foo() -> int = 0;

};

struct Derived : Base {

auto foo() -> int override { return 77; }

};

auto bar() -> int {

Derived derived;

return derived.foo(); // compiler knows this is Derived::foo

}

The compiler is able to devirtualize even through a base pointer, as long as it can track the allocation and prove there is only one possible concrete type. The problem is that with traditional compilation, object files are created per translation unit (TU)—compiled and optimized in isolation. The linker simply stitches those objects together, so cross-TU optimizations are inherently limited. That’s where compiler flags are useful.

-fwhole-program- tells the compiler “this translation unit is the

entire program.” If no class derives from

Basein this TU, the compiler is free to assume nothing ever does, and can devirtualize calls onBase. -flto- link-time optimization. Keeps an intermediate representation in the object files and optimizes across all of them at link time, effectively treating multiple source files as a single TU.

On the language side, final is a lightweight way to give the compiler

the same guarantee for specific methods

class Base {

public:

virtual auto foo() -> int;

virtual auto bar() -> int;

};

class Derived : public Base {

public:

auto foo() -> int override; // override

auto bar() -> int final; // final

};

auto test(Derived* derived) -> int {

return derived->foo() + derived->bar();

}

Here, foo() can still be overridden, so derived->foo() remains a

virtual call. However, bar() is marked as final, so the compiler

emits a direct call even though it’s declared virtual in the base

test(Derived*):

push rbx

sub rsp, 16

mov rax, QWORD PTR [rdi]

mov QWORD PTR [rsp+8], rdi

call [QWORD PTR [rax]] // Virtual call

mov rdi, QWORD PTR [rsp+8]

mov ebx, eax

call Derived::bar() // Direct call

add rsp, 16

add eax, ebx

pop rbx

ret

Static polymorphism §

When the compiler can’t devirtualize, one option is to use static

polymorphism instead. The canonical tool for this is the Curiously

Recurring Template Pattern3 3

The curiously recurring template pattern is an idiom where a

class X derives from a class template instantiated with X itself as a

template argument. More generally, this is known as F-bound

polymorphism, a form of F-bounded quantification.

(CRTP). With CRTP, the base class is

templated on the derived class, and invokes methods on it via

static_cast—no virtual keyword involved

template <typename Derived>

class Base {

public:

auto foo() -> int {

return 77 + static_cast<Derived*>(this)->bar();

}

};

class Derived : public Base<Derived> {

public:

auto bar() -> int {

return 88;

}

};

auto test() -> int {

Derived derived;

return derived.foo();

}

With -O3 optimization, the compiler inlines everything and

constant-folds the result. No vtable, no vptr, no indirection.

Fully optimized4 4

The trade-off is that each Base<Derived> instantiation is a

distinct, unrelated type, so there’s no common runtime base to upcast

to. Any shared functionality that operates across different derived

types must itself be templated.

call.

test():

mov eax, 165 // 77 + 88

ret

Deducing this. C++23’s deducing this keeps the same static-dispatch

model but makes it easier to write. Instead of templating the entire

class (and writing Base<Derived> everywhere), you template only the

member function that needs access to the derived type, and let the

compiler deduce self from *this

class Base {

public:

auto foo(this auto&& self) -> int { return 77 + self.bar(); }

};

class Derived : public Base {

public:

auto bar() -> int { return 88; }

};

This yields identical optimized code: foo is instantiated as

foo<Derived>, and the call to bar is resolved statically and

inlined.