Optimizing a Lock-Free Ring Buffer

A single-producer single-consumer (SPSC) queue is a great example of how far constraints can take a design. In this post, you will learn how to implement a ring buffer from scratch: start with the simplest design, make it thread-safe, and then gradually remove overhead while preserving FIFO behavior and predictable latency. This pattern is widely used to share data between threads in the lowest-latency environments.

What is a ring buffer? §

1

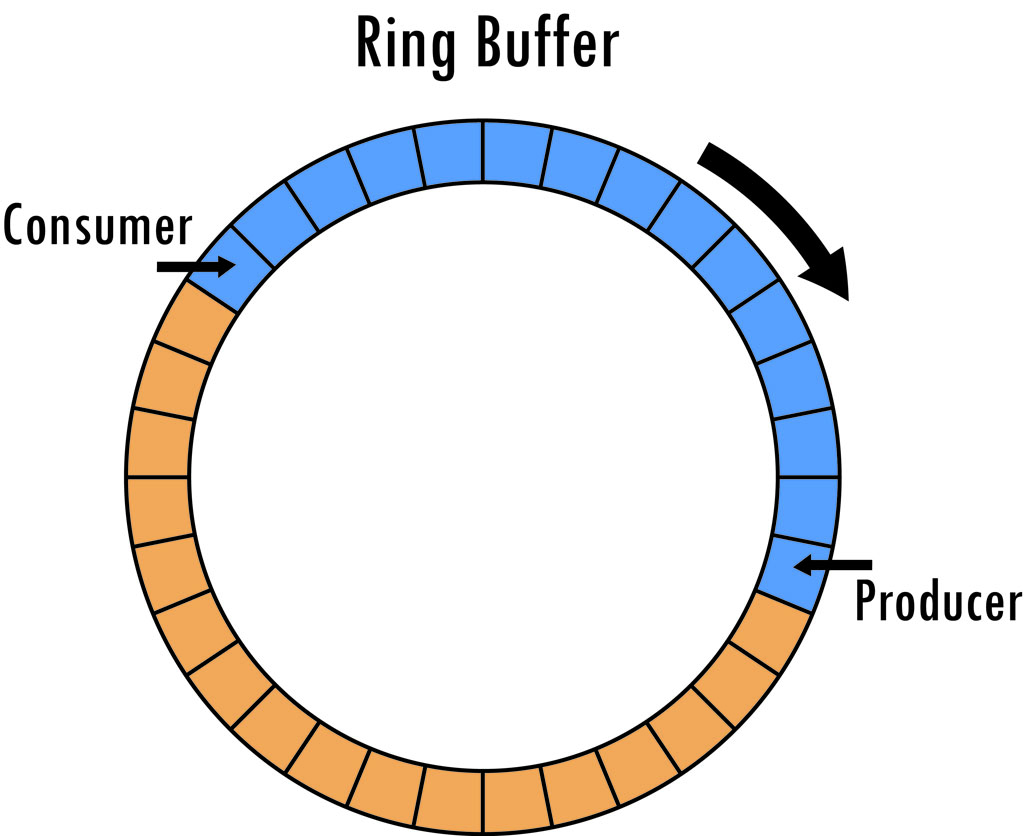

Ring buffer with 32 slots. The

producer has filled 15 of them, indicated by blue. The consumer is

behind the producer, reading data from the slots, freeing them as it

does so. A free slot is indicated by orange.

You might have run into the term circular buffer, or perhaps

cyclic queue. These are simply other names for a ring buffer: a queue

where a producer generates data and inserts it into the buffer, and a

consumer later pulls it back out, in first-in-first-out order.

Ring buffer with 32 slots. The

producer has filled 15 of them, indicated by blue. The consumer is

behind the producer, reading data from the slots, freeing them as it

does so. A free slot is indicated by orange.

You might have run into the term circular buffer, or perhaps

cyclic queue. These are simply other names for a ring buffer: a queue

where a producer generates data and inserts it into the buffer, and a

consumer later pulls it back out, in first-in-first-out order.

What makes a ring buffer distinctive is how it stores data and the constraints it enforces. It has a fixed capacity; it neither expands nor shrinks. As a result, when the buffer fills up, the producer must either wait until space becomes available or overwrite entries that have not been read yet, depending on what the application expects.

The consumer’s job is straightforward: read items as they arrive. When the ring buffer is empty, the consumer has to block, spin, or move on to other work. Each successful read releases a slot the producer can reuse. In the ideal case, the producer stays just a bit ahead, and the system turns into a quiet game of “catch me if you can,” with minimal waiting on both sides.

Single-threaded ring buffer §

Let’s start with a single-threaded ring buffer, which is just an

array2 2

By using std::array we are forcing clients to define the buffer

size as constexpr. It’s also common to use instead a std::vector to

remove that restriction. A further optimization is to constrain the

capacity to a power of two, allowing wrap-around via bit masking head & (N - 1) instead of a branch.

and two indices. We leave one slot permanently unused to

distinguish “full” from “empty.” Push writes to head and advances it;

pop reads from tail and advances it.

template <typename T, std::size_t N>

class RingBufferV1 {

std::array<T, N> buffer_;

std::size_t head_{0};

std::size_t tail_{0};

};

We can now implement the push (or write) operation3 3

Note how one item is left unused to indicate that the queue is

full. When head_ is one item ahead of tail_, the queue is full.

auto push(const T& value) noexcept -> bool {

auto new_head = head_ + 1;

if (new_head == buffer_.size()) [[unlikely]] { // Wrap-around

new_head = 0;

}

if (new_head == tail_) [[unlikely]] { // Full

return false;

}

buffer_[head_] = value;

head_ = new_head;

return true;

}

Next we implement the pop (or read) operation4 4

Again note that head_ == tail_ indicates that the queue is

empty.

auto pop(T& value) noexcept -> bool {

if (head_ == tail_) [[unlikely]] { // Empty

return false;

}

value = buffer_[tail_];

auto next_tail = tail_ + 1;

if (next_tail == buffer_.size()) [[unlikely]] { // Wrap-around

next_tail = 0;

}

tail_ = next_tail;

return true;

}

Thread-safe ring buffer §

You probably already noticed that the previous version is not

thread-safe. The easiest way to solve this is to add a mutex around

push and pop.

template <typename T, std::size_t N>

class RingBufferV2 {

std::mutex mutex_;

auto push(const T& value) noexcept -> bool {

auto lock = std::lock_guard<std::mutex>{mutex_}; // Thread-safe

// ...

}

auto pop(T& value) noexcept -> bool {

auto lock = std::lock_guard<std::mutex>{mutex_}; // Thread-safe

// ...

}

};

It’s correct and often fast enough: around 12M ops/s5 5

Compiled with clang compiler with highest -O3 optimization

level, and -march=native -ffast-math. Consumer and producer threads

are pinned to dedicated cores (Intel Core Ultra 5 135U). See benchmark.

on

consoomer hardware. However, it pays for mutual exclusion even though

the producer and consumer never write the same index. The ownership is

asymmetric: the producer is the only writer of head, and the consumer is

the only writer of tail. That asymmetry is the lever to remove locks.

Lock-free ring buffer §

We can remove the locks by using atomics instead6 6

Note that we are manually aligning alignas the atomics to

ensure they fall in different cache lines (commonly 64 bytes). This

prevents false sharing, hence optimizes CPU cache usage.

template <typename T, std::size_t N>

class RingBufferV3 {

std::array<T, N> buffer_;

alignas(std::hardware_destructive_interference_size) std::atomic_size_t head_{0};

alignas(std::hardware_destructive_interference_size) std::atomic_size_t tail_{0};

};

The push implementation becomes

auto push(const T& value) noexcept -> bool {

const auto head = head_.load();

auto next_head = head + 1;

if (next_head == buffer_.size()) [[unlikely]] {

next_head = 0;

}

if (next_head == tail_.load()) [[unlikely]] {

return false;

}

buffer_[head] = value;

head_.store(next_head);

return true;

}

And the pop implementation

auto pop(T& value) noexcept -> bool {

const auto tail = tail_.load();

if (tail == head_.load()) [[unlikely]] {

return false;

}

value = buffer_[tail];

auto next_tail = tail + 1;

if (next_tail == buffer_.size()) [[unlikely]] {

next_tail = 0;

}

tail_.store(next_tail);

return true;

}

Simply removing the locks yields 35M ops/s, more than double the

throughput of the locked version! You have probably noticed that we are

using the default std::memory_order_seq_cst memory order for loading /

storing the atomics, which is the slowest. Let’s manually tune the

memory order7 7

release ensures prior writes are visible to threads that

acquire the same variable. Both sides use relaxed for their own

index since no other thread writes to it.

auto push(const T& value) noexcept -> bool {

const auto head = head_.load(std::memory_order_relaxed);

auto next_head = head + 1;

if (next_head == buffer_.size()) [[unlikely]] {

next_head = 0;

}

if (next_head == tail_.load(std::memory_order_acquire)) [[unlikely]] {

return false;

}

buffer_[head] = value;

head_.store(next_head, std::memory_order_release);

return true;

}

auto pop(T& value) noexcept -> bool {

const auto tail = tail_.load(std::memory_order_relaxed);

if (tail == head_.load(std::memory_order_acquire)) [[unlikely]] {

return false;

}

value = buffer_[tail];

auto next_tail = tail + 1;

if (next_tail == buffer_.size()) [[unlikely]] {

next_tail = 0;

}

tail_.store(next_tail, std::memory_order_release);

return true;

}

Rerunning the benchmark now gives an astonishing 108M ops/s—3x the previous version and 9x the original locked version. Worth the effort, right?

Further optimization §

We already have a fast ring buffer, but we can push it further. The

main slowdown comes from the reader and writer constantly touching each

other’s indexes. That makes the CPU bounce cache lines8 8

It’s useful to observe the number of cache misses with perf stat -e cache-misses; they are greatly reduced in this approach.

between cores,

which is expensive.

To reduce this, the reader can keep a local cached copy9 9 This advanced optimization was initially proposed by Erik Rigtorp. of the write index, and the writer keeps a local cached copy of the read index. Then they don’t need to re-check the other side on every single operation: only once in a while.

template <typename T, std::size_t N>

class RingBufferV5 {

std::array<T, N> buffer_;

alignas(std::hardware_destructive_interference_size) std::atomic_size_t head_{0};

alignas(std::hardware_destructive_interference_size) std::size_t head_cached_{0};

alignas(std::hardware_destructive_interference_size) std::atomic_size_t tail_{0};

alignas(std::hardware_destructive_interference_size) std::size_t tail_cached_{0};

};

The push operation is updated to first consult the cached tail

tail_cached_ and if that fails retry after updating the cache

if (next_head == tail_cached_) [[unlikely]] {

tail_cached_ = tail_.load(std::memory_order_acquire);

if (next_head == tail_cached_) {

return false;

}

}

The pop operation is updated in a similar way to first consult the cached head

if (tail == head_cached_) [[unlikely]] {

head_cached_ = head_.load(std::memory_order_acquire);

if (tail == head_cached_) {

return false;

}

}

Throughput is now 305M ops/s—nearly 3x faster than the manually tuned lock-free version and 25x faster than the original locking approach.

Summary §

If you want to reproduce these results, run the included benchmark

compiled with at least -O3 optimization level.10 10

Alongside -O3, the benchmark was compiled with -march=native

and -ffast-math, though these flags shouldn’t make a difference here.

The benchmark

pins the producer and consumer threads to dedicated CPU cores to

minimize scheduling noise.

| Version | Throughput | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | N/A | Not thread-safe |

| 2 | 12M ops/s | Mutex / lock |

| 3 | 35M ops/s | Lock-free (atomics) |

| 4 | 108M ops/s | Lock-free (atomics) + memory order |

| 5 | 305M ops/s | Lock-free (atomics) + memory order + index cache |

Long live lock-free and wait-free data structures!